Yearning to Breathe Free

How one style of music inspired a piece and changed my work

We all have “a-ha” moments in our lives – moments where something we had been struggling to comprehend or execute clicks into place, or where our understanding or appreciation of something is greatly increased by just one additional idea. These can be important moments in all areas of our lives, from learning and schooling to personal relationships. In pursuit of artistic endeavors, these moments can be of special importance. The creative process is far from linear.

Additionally, people may have greater or lesser response different explanations of the same idea, depending on their frame of reference and how they best process information. I learn this repeatedly while teaching music theory, for instance – I regularly give three or four different explanations of how to identify chords or intervals so that students can use the one that suits them best.

In creative pursuits, one of the most powerful tools at the disposal of any person is their unique set of personal experiences – from their culture to their family background to the historical and political events which have signposted their past. No two individuals have lived the exact same life. Therefore, no two individuals think alike or make the same creative free associations.

It is important to stay open to these “a-ha” moments because you never know when and from where they will come, and any given connection between two disparate ideas may be visible only to you.

In my musical life, there are certainly particular pieces of music, as well as entire styles of music-making, which shed light in ways that profoundly influenced the course of my work.

Perhaps the earliest one for me was my exploration and absorption of The Lord of the Rings soundtracks. I became enamored with this music in middle school, when I had already been playing classical piano for about six years. The steady diet of Bach, Beethoven and Chopin drilled the major/minor dichotomy into my mind from a young age. By age twelve, I already had some misgivings about this harmonic system and its rigid categories. At that impressionable age, the releases of the LOTR movies in the early 2000s were perfectly timed to make an impact. The folk-inspired sounds of those soundtracks were a watershed moment in my young musical life. To put it as I did in my mind at the time, the music confirmed for me that there was a world that existed in between and outside of major and minor. This was a world I was much more interested in inhabiting than the world of 19th-century tonality, and I have been living in that world in one way or another ever since. (Perhaps a blog entry from another time.)

This is a more specific story of how an “a-ha” discovery of a style of music led to one specific piece.

What is shape note music?

Sacred Harp music, or shape note music, is a performance tradition connected to a body of musical work which traces its roots to singing schools in New England in the early history of the United States. After its diffusion from that area, it took particularly strong root in the American South, and is still practiced by enthusiasts around the United States and across the world. While the music is sacred Christian music in its content, many of those who perform it do not necessarily share its religious convictions, and it is not generally performed in the context of a church service.

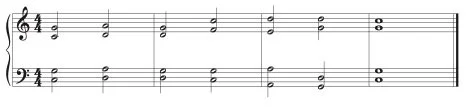

The term “shape note” refers to the notation style which was and is used for this body of musical work. This music uses a notation system essentially the same as any piece of Western sheet music, but with noteheads that are shaped differently based on which note of the scale they are within the music’s key:

This provides an extra mnemonic to facilitate sight reading.

Sacred Harp gatherings are for the expressed purpose of communal singing. They are not considered performance for an audience, nor rehearsal for a future performance. Attendees sit in a square formation, each voice part taking one side of the square, facing inward. A leader stands in the middle of the square and calls tunes, gives starting pitches, and conducts a beat in a straightforward fashion. Members of the gathering often take turns leading.

Before singing the tune on the written lyrics, it is usually sung through once on a simplified solfege consisting of four syllables.

The Sacred Harp is the collection of music traditionally used at these gatherings. Historically, there have been other collections as well, such as William Walker’s Southern Harmony.

Musically speaking, the compositions contained in these collections are an intriguing mix of sounds. They range from four-part, homophonic (i.e. all the voices have the same words and rhythms) settings that look much like what you might find in a standard hymnal, to highly contrapuntal “fuging tunes” and multi-sectional works. Traditionally, both men and women sing the soprano and tenor parts, creating octaves throughout the music, and the tenor part is considered the melody. However, the music is broadly considered to be polyphonic (comprised of independent, equal parts) and all parts are designed to be active, engaging lines in their own rights.

As noted in the most recent addition of The Sacred Harp, late eighteenth-century New England composers such as William Billings were educated in the harmonic practices of European classical composers and (in some ways) followed in their footsteps, using “tertian harmony” – music which uses thirds on top of thirds to create the major and minor triads and seventh chords we hear throughout 18th and 19th century classical music, as well as popular songs and many other traditions and genres. However, many people who compiled materials for early nineteenth century singing schools were not educated in European classical music and tended to use harmony which was largely based around fourths and fifths – also called quartal harmony in contemporary music theory.

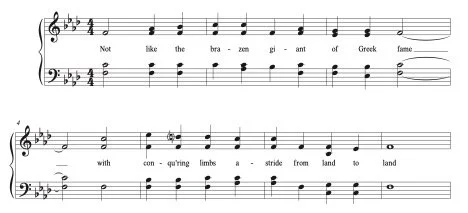

For example, listen for the differences between these two excerpts which have the same top line melody:

The first version uses tertian harmony, along the lines of something an 18th century European composer may have written. The second excerpt uses fourths and fifths instead. Without thirds in the chords, the music does not sound like it is in the major mode or the minor mode because the ear does not have enough information to pick one. The resonance of fourths and fifths create an openness in the sound that is not always present in tertian harmony.

These two sides of the Sacred Harp coin have intermingled throughout the tradition’s history in various ways to produce a unique harmonic fingerprint. It sometimes has the veneer of classical harmony at first glance, but breaks every harmonic guideline in a music theory textbook on further inspection. William Billings stated his rebellion against European practice at the time: “I don’t think myself confined to any rules of composition laid down by any who went before me.” Many of the more quartal or folk-like tunes were originally in three parts, with an alto part added at some point after the first edition. Many Sacred Harp tunes, even those with more classical-style harmony throughout, end on open fifths without thirds. This stands in contrast to classical pieces and hymns, which rarely leave out the third of a chord at any point in the music. While the tenor part is generally considered the melody, all parts are usually equally active with plenty of skips and leaps, creating interesting musical lines in their own rights. This stands in contrast to four-part writing taught in most music theory classrooms, which emphasize smooth lines wherever possible.

Of course, this is all to say nothing of performance practice, which is perhaps the most well-known facet of Sacred Harp music. Singers sing in a belting, energetic tone which is quite different from a classical choral performance:

The musical results of the marriage between the content of these scores and the style of performance reminds me of just how many musical possibilities exist without the need for dense, complex chords and harmonic processes.

When I sit down to write a piece, after taking time to absorb and contemplate the text, the first thing I do is create a harmonic outline of the piece. That’s just the way I work best. I plan out the overall scheme of how the harmony will flow and what chords I will use to create the sound of the music. Shape note music has enhanced my harmonic judgement and self-control. When I write straightforward chord progressions now, I often begin and end with a fifth instead of a full chord with a third present. I have also learned to consider how each chord is voiced in a more detailed way, taking careful stock of which chords have a third in them and which don’t, which notes of the chord are on the top and the bottom, and how factors such as these affect the direction and momentum of the phrase.

Some of these questions are reminiscent of guidelines one learns while studying four-part writing in a music theory class, though with quite different criteria and musical outcome. Writing that way never felt like me. Studying this music has allowed me to take these principals and make them my own. It has helped me find ways of creating more straightforward chord progressions in my own way, as well as saving more dramatic or dissonant harmonies for key points in a piece instead of exhausting all my harmonic possibilities right away. It has given me a true “lightbulb moment” in my work.

I am certainly not the first composer to take a great deal of influence from this music. For example, William Duckworth, post-minimalist composer famed for his Time Curve Preludes, saw parallels between minimalist processes and layering and Sacred Harp music. In his work Southern Harmony, he uses layering, sustained pitches, and counterpoint to reimagine traditional shape note tunes.

In discussing a commission for Westminster Choir College’s Williamson Voices with their conductor Dr. James Jordan, we bonded over our mutual love of Duckworth’s Southern Harmony and decided to take our piece in a similar direction. However, I did not want to rehash an existing tune for a commissioned work. I felt the occasion deserved a purely original composition.

Breathe Free

Nearly all choral music starts with text, in one way or another. Therefore, after having determined our musical point of inspiration, the immediate next step was to choose a text.

Sacred Harp music is generally a sacred music tradition. The lyrics are usually religious in content, with a clear strophic form like a hymn. However, Westminster Williamson Voices is a college ensemble, not a church one, and I did not wish to write something sacred for this commission. I wanted something more humanistic, but also iconic, with enough gravity to mirror the intensity of the religious imagery and fervor of many Sacred Harp tunes. In order to reflect the Shape Note influence, it also needed to be strophic with a strong rhyme scheme.

This led me to Emma Lazarus’s “The New Colossus.” It doesn’t get much more iconic than this text, at least in the United States – the words are literally etched on one of the most recognizable symbols of the country and the most idealized version of its values. As a sonnet, the words have a strong rhyme scheme and meter with ten syllables per line, an odd number in musical terms. Many Sacred Harp tunes also have odd meters. For a work inspired by a tradition that is distinctly American, this poem seemed like the perfect choice.

However, I broke my own rule by choosing this text. Usually, I strive for creative text choices which have not been used before to keep my work fresh and meaningful for performers and audiences alike. In fact, composers continuing to set texts which have already been set ad nauseum is usually a bit of a pet peeve of mine. Not only are there many settings of this poem already, but there are many settings that I love. Ed Frazier Davis, Saunder Choi, and Caroline Shaw all have stunning settings of this sonnet (though Shaw takes many liberties, describing her setting as a “response”). However, this only goes to show what an icon in American culture this text is.

I approached this piece as if I were arranging a pre-existing Shape Note tune, as I have done before, except in this case, I wrote the tune.

This piece was written and recorded during the thick of the pandemic, so it was important to assume a certain amount of latency in the performance situation. When singers are physically farther apart, or recording different parts remotely, precise timing and synchronization is not possible. However, this presents some exciting textural possibilities that aren’t so far outside the realm of the expressive qualities and performance practices of Sacred harp music.

Ultimately, the idea that prevailed throughout this piece and its manipulation of this tune was sustain. The use of sustained notes pulled from within the tune underpins several of William Duckworth’s pieces as well:

The result is, I hope, a piece that uses spacious sounds to enhance the tune in a way that honors the text, its ideals, and its place as an icon in American popular culture. I have also incorporated sections of the piece where the choir members sing their parts independently of each other in their own time, which arguably democratizes the performance, at least just a touch.

Breathe Free is now available for performance; purchase from GIA Publications: https://www.giamusic.com/store/resource/breathe-free-print-g10470

You can listen on Spotify, or wherever you listen to music: https://open.spotify.com/album/02cU6U8eeASFlRmVX7nIHi?si=PBVDBUzdQ7ehNO3Cz-DwGg

Many thanks to Dr. James Jordan, Westminster Williamson Voices, and GIA Publications for their hard work and dedication in bringing this piece to life!