The Burning Ladder

My setting of “The Burning Ladder” is now officially complete. The piece has been an absolute pleasure to work on, the perfect “passion project” to stretch my text-setting muscles resulting in what (I think) is a unique work, which is always important to me. Thank you so much to the ensembles participating in this consortium, I am so excited to be sharing the work with you all and I can’t wait to hear the performances of both “The Burning Ladder” and “The Stars Now Rearrange Themselves.”

Last week, I discussed the poetic works of Dana Gioia and the textual origins of my piece. I focused on how I went about setting this particular text, and how that dictated the textures throughout the piece in particular.

After I feel that I’ve absorbed as much of what the text has to offer as I can, I almost always start a piece by defining my most basic chordal building blocks and sketching a harmonic outline. I consider my conflicted-ridden usage of tonal and modal harmony to be the most defining feature of my music. But what is that going to look like for a text as intricate as “The Burning Ladder”? I am already using some busier textures to paint the text in this piece; I don’t want to distract from this poem by going crazy with crunchy chords and complex tonal relationships throughout the whole thing.

Scales and Ladders

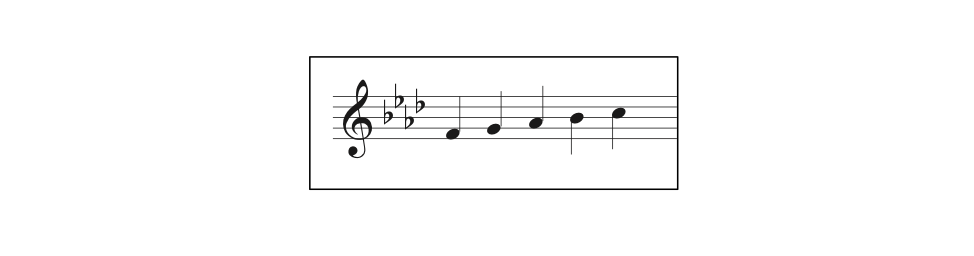

The piece is about a ladder. What better place to start than a scale? Melodically-speaking, one of the most basic units in music:

These are the first five notes of the fiery F minor scale, not a key I use too often. Treating these first five notes as a unit, leaving off the top two, gives this little cell clear starting and stopping points. The first five notes of a scale in succession also recall rudimentary piano exercises, or anything that can be played simply with the five fingers on one hand. It feels elementary – perfect as the most basic building block for my harmonies and harmonic structure in this piece.

What can I do with this most basic musical idea? Scales are generally a melodic thing, with harmonies being pulled from select notes of the scale. But, to start, I can easily do this:

What better way to turn a melodic fragment into harmony than using it to create a cluster? I can pull out all of the dissonance I need from this stack of notes, with all its nuances and possible subsets, to create an appropriately dramatic setting of this text. Additionally, while tone clusters may sound thorny and look difficult on the page, if approached in a stepwise manner they can be highly idiomatic for a choral group, hence their popularity. The distinct shimmer of their dissonance helps the singers lock them into tune. Going back to the textures I discussed last week, I can use the repeated rhythms and short bits of text to build up this cluster one note at a time. This will form the first section of the piece, and inspire the rest.

I’ve now used this F minor scale in a couple of different ways, but without something more blurry to alternate with these precise rhythms, they might lose their potency. So, I arrive at another way to think of this short scale:

Sometimes, scales function simply as passing notes – a stepwise way of getting from note A to note B. We can also blur these steps with a glissando from note A to note B instead. Same linear destination, but the journey sounds radically different. While the sopranos and altos begin singing the text and building up this tonal cluster over the course of the first few lines of the poem, this glissando will be sung by the tenors and basses to alternate with the stops and starts of their short phrases. However, I will up the ante by taking Joby Talbot as a point of inspiration (on a much smaller scale) and allowing the basses each to take the glissando at their own time and pace within the passage. Instead of performing the glissandi alongside the basses, the tenors will be singing this same rise, but in the discrete pitches of the scale. If this first section piece wasn’t fiery enough for the text yet, it certainly should be now!

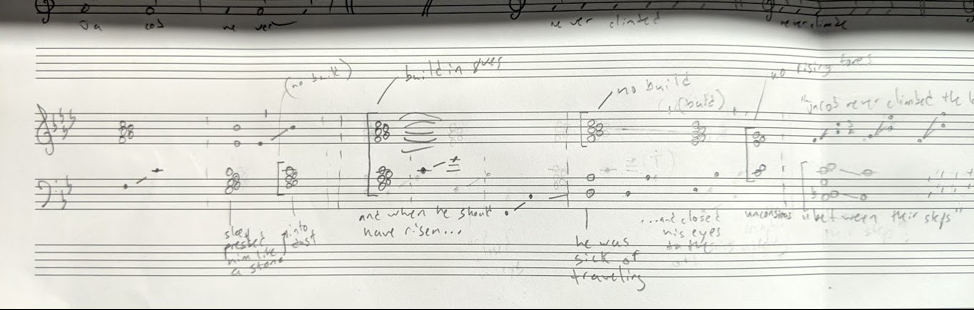

These simple ideas give me the entire first section of the piece. As I said before, one of my main starting points with a piece is almost always some sort of harmonic outline. Not only do they look cool when I post them on Instagram, but they do in fact serve an important purpose in my creative process, helping me construct the form and pacing of the whole piece:

My harmonic sketch of the first ~2/3 of “The Burning Ladder,” finalized after many drafts.

A short harmonic outline of the climax of the piece, which stayed more-or-less the same throughout different sketches.

While the scale motive I’m using is always rising, the harmonic moves that happen before the climax of the piece are all downward. The first move after the initial buildup is down a step to E flat major, providing some major-chord relief from the dissonance and painting the image of Jacob sleeping. As Tom discussed in his blog, Dana’s writing often seems to operate on multiple planes of existence or thought, which implies these parallel shifts to different harmonic levels within the music. In my piece, I make these shifts in a very stepwise way, in keeping with the importance of scales throughout the piece.

I didn’t follow this outline to a T, but I did follow a good deal of it, including the downward parallel shifts in the harmonies leading up to the climax of the piece, when the harmony finally truly moves upward to G flat major. This is the first time there is an accidental anywhere in the piece, unusual for a piece of mine.

An interesting observation for any music theory nerds out there: the first major harmonic shift of Tom’s piece is also to the “flat 2,” an enharmonic shift to A minor from our home of G# minor. We might call this a Neapolitan chord in traditional harmonic analysis – a major triad based on the flatted second scale degree, usually in a minor key – though in Tom’s case it is a minor flat 2 instead, requiring additional accidentals. In “The Burning Ladder,” this shift arrives at a major flat 2, closer to a traditional Neapolitan chord, though used completely differently than in 19thcentury common practice tonal music. However, the final verse of my piece “The Angel with the Broken Wing” makes this same shift to minor flat 2, D flat minor (mostly) in the key of C minor. Tom and I wrote our Scattered Light pieces very independently, and I wrote “Angel” over a year ago, though I only just received its first recording. Perhaps something about Dana’s writing implies this particular kind of shift, rooted in 19th century common practice chromaticism but used much differently in the hands of us contemporary choral composers.

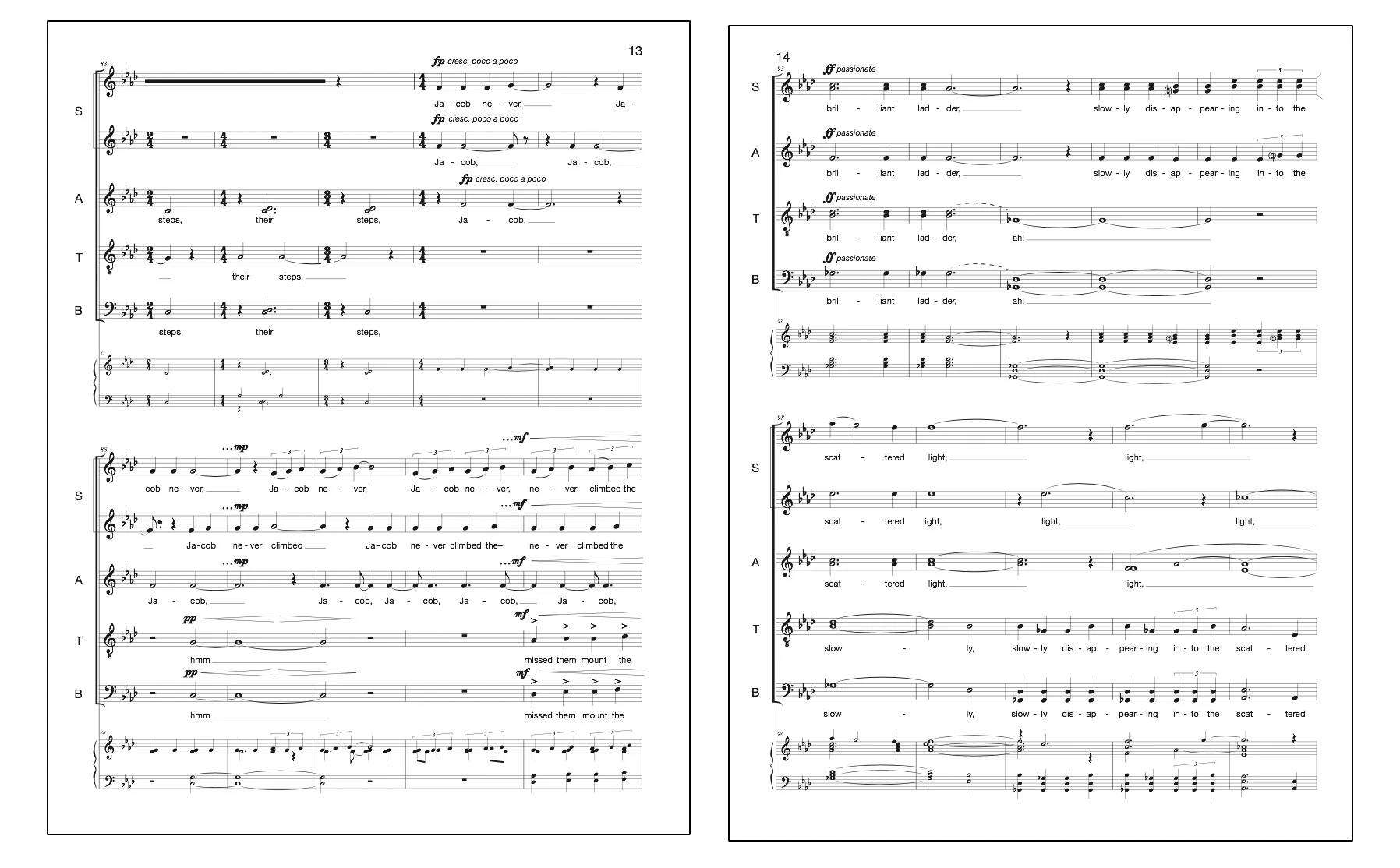

I contemplated a few different ways of ending this piece, but I settled on a mirroring of the opening with a few alterations. After all, Jacob has perhaps been changed by his vision in his own mind but remains right where he started in the world. I shifted to C minor instead of F minor, and showed the gravity of the final lines by giving the basses downward glissandi instead of upward, the first time this happens in the piece. All of the textural passages setting the line “Jacob never climbed the ladder burning in his dream” are repeated, but in reverse order, leaving the ending with simple, haunting repetitions of Jacob’s name, just as we started.

I will conclude by saying that, while Tom and I worked on these pieces very independently as I said, I could not be more thrilled with the way these two pieces seem to work together. Tom and I have both noted how well these pieces can sit side by side. Clearly we know each others’ styles quite well at this point, but this is also a testament to the strength of Dana’s writing and its clarity of vision. I am so proud of my fiancé for the setting he has produced, which is full of drama and passion and yet profoundly sensitive to the nuances of this mysterious text. I cannot wait to hear all of the participating ensembles interpret this music, and heartfelt thanks to everyone who has supported this project!